There’s a paragraph on page two of the instruction manual for the Anko BL9706-CB blender, that states:

“To prevent damage to the electric motor, the maximum operating time is 1 minute. Allow it to rest for the least 2 minutes before using it again. After 5 cycles of operation, allow the blender (electric motor) to cool down to room temperature. Allow it to cool down for approx. 30 minutes before using it again.”

So you can blend, but not too much. Clearly, the motor (and most likely the rest of the appliance) isn’t built to last.

The Kmart Facebook page champions its “Low prices for life”. The blender certainly has a low price ($29), but its life is unlikely to be long.

To find out how this $29 blender lasts in daily use, I bought one and set about making smoothies: my healthy breakfast for the foreseeable future would be a thick bowl of frozen banana and mango, spinach, yogurt and matcha powder.

How the blender performed

The seemingly impossibly low price generated a lack of confidence around the Consumer NZ office. Talk was that this cheap blender would fail quickly – and I should keep a fire extinguisher handy! At the very least, most people expected it to fail as soon as I ramped up my testing from making a daily smoothie to blatantly disregarding the warning in the manual.

I started by seriously over-blending a smoothie for eight minutes. The motor housing got warm (about 45°C), but the blade kept spinning. Now, after a month making five or six thick smoothies each week, the blender is still working. To be honest, I’m not surprised – if these Anko models were failing after just a month, Kmart would soon pull them from shelves.

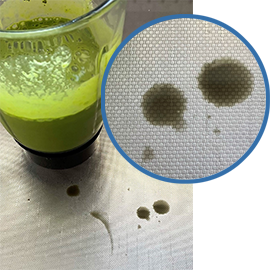

However, it’s not all good news. In the first week the blade worked loose in its housing. Tell-tale signs were drips of a worrying green-black liquid from the base of the jug. Perhaps the Anko will hang on for a while yet – but yuk – those drips don’t fill me with hope.

No repairs for you

The blade is removeable for cleaning, so it would be a doddle to replace. If it failed on a pricier model, I’d expect a spare part to be readily available. However, buying a cheap product from a store known for cheap products means support is unlikely.

I’ve previously contacted Kmart to see if I could get spare parts for an Anko kettle. It said:

Anko blender's faulty part.

“We do not offer spare parts or warranty repair service [for any kettles sold] at Kmart. It is not possible to do so, within our everyday low pricing model.”

My blender has a 12-month warranty. I contacted Kmart customer services asking for a replacement part. The answer I received avoided the subject:

If your blender is less than 12 months old, please take it along with your receipt to your local Kmart store for an exchange or refund.

I took my blender (and proof of purchase) to my local Kmart store, explained the problem and repeated my request for a replacement part. I was told no parts were available and offered a refund. My Anko blender is toast if a part costing a few cents fails? That’s not good enough. I don’t want to junk an otherwise fine appliance because one small, easy-to-replace part has failed.

I asked Kmart what happened to faulty or unwanted appliances returned to its stores. A customer services rep told me “returned items are either refurbished or recycled for parts”.

Manufacturers, retailers and consumers have to stop this cycle of making, selling, buying and binning cheap junk.

There is a better way: repairability

KitchenAid coupling replacement.

For this trial, I put my usual KitchenAid blender aside. It’s at least 17 years old – I know because it still has its original UK plug and I moved to New Zealand in 2004.

It’s been repaired three times – I’ve replaced the blade and its seal, and a rubber coupling between the driveshaft and blade has failed twice. Each coupling fix, the latest six months ago, used a $15 part fitted in two minutes. The part is designed to be easy to replace. It protects other parts, such as the motor or driveshaft from damage, so failure doesn’t become a catastrophic problem.

Of course, my blender cost much more than $29 – the equivalent current model (the Diamond Artisan) sells for $349. But, even factoring in spare parts, and assuming it’s been in-use for 12 years (it has been stored for some of its life), it’s cost me about the price of an Anko blender each year. If an Anko blender lasted much more than a year in my kitchen, I’d be very surprised.

So I estimate that repairing my blender is likely to have saved the resources needed to make anything up to 11 additional blenders, their packaging and the transport emissions to get them here from China.

Good design costs almost nothing

Anko BL9706-CB blender

Designing and making products more durable and repairable means using better materials where it matters, improving quality control, and designing critical parts to be user-replaceable should they fail. A $29 blender that lasts a lifetime might be a pipe dream, but a $50 model that lasts for five or six years isn’t impossible.

The bigger problem is brands not having the desire and business model to make durability a priority, or committing to support their products after they’ve been sold.

For companies focused solely on low prices, such as Kmart, it’s cheaper and easier to replace an entire product than fix it. The few that fail within warranty hit Kmart’s bottom line, but the majority that hang on just a bit longer don’t cost them a cent. This means there’s no incentive to make a blender that lasts for 12 years. When its appliances die – it’s not Kmart’s problem.

E-waste product stewardship scheme in the works

Thankfully, change is coming. Last year the government announced electrical and electronic products (anything with batteries or a plug) as one of six priority product classes that’ll get a mandatory product stewardship scheme. That means everyone involved in making, selling and using an appliance will have to take some responsibility for dealing with it when it is no longer wanted, or it dies and becomes ‘e-waste’. The reality is, users (in other words, consumers) already pay for end of use management – whether it’s through a fee to recycle it as e-waste, or to junk it in landfill – whereas most of those who make and sell stuff (which is manufacturers, distributors and retailers) get off scot-free. A product stewardship scheme aims to fix this imbalance.

At its simplest, a scheme means producers and distributors, such as Kmart, will likely pay a small fee for appliances they import and sell in New Zealand. Money raised will then be used to pay for e-waste collection and recycling activities, along with education and awareness of the schemes.

However, a well-designed scheme could also incentivise producers to supply more durable products and offer more after-sales support. For example, a mandatory scheme could incentivise good product design through reduced fees – if it’s built to last and the embedded resources can be safely and easily recovered then this could and should be rewarded.

Inexpensive improvements, such as making troubleshooting resources available to owners needing to fix faults, or access to consumer-replaceable spare parts, could make even a $29 blender last longer. It wouldn’t cost much for Kmart to supply a replacement blade. If doing so meant it reduced its cost of dealing with dead blenders, acting responsibly might become the more cost-effective option to choose in the long run – even for a store championing its everyday low prices.

Change won’t happen overnight. We’re a long way from seeing the end of cheap, unsupported, built-to-fail appliances, but we’re moving in the right direction.

What's Kmart doing about it?

On its website, Kmart states it’s transitioning to be part of a circular economy (an economic system that aims to reduce waste). The retailer is also committing to train staff on circular economy principles. This year it will launch a plan to provide customer access to in-store drop-off, reuse or recycling options. From July 2022, it says its bedding, towels and clothing will include washing labelling aimed at minimising water and energy use.

It’s positive that Kmart is committing to change, but its commitments push responsibility on to consumers to do the right thing.

We’ve asked Kmart to clarify what actions it is taking to make its appliances more durable and repairable.

How long should a product last?

In our latest survey, 54% of consumers agreed that “the warranty period was a good indication of how long a product will last”. I had to read that number twice, surely no-one would expect a product to fail right after its warranty expires?

Typically one or two years, the warranty is the most basic guarantee of life. It’s the period in which the manufacturer has calculated it’s economic for it to cover all repairs and replacements of faulty products. That means it’s the period in which it expects to see few failures. A company will tightly define its warranty conditions: prescribing how you are expected to use the product and what you can’t do to it without voiding its warranty.

Realistically, you should expect a product to last well beyond its warranty period.

You choose: 10 years or 10% cheaper?

For a promotion in 2020, Miele offered a 10-year warranty on most of its large appliances. It said if anything went wrong it would put it right. As an alternative, consumers were offered a 10 percent discount on the usual selling price, but with the regular two-year warranty.

Many people, knowing Miele were confident enough to stand behind its product for 10 years, chose the discount. They were confident the appliance would be durable and they got a better price.

In our survey, four in five consumers strongly agreed that they’d pay more for an appliance that lasted longer. But how do you know how long an appliance is likely to last, if the warranty period isn’t a good indication?

Durability rating labels

That’s where we think manufacturers should state the expected lifetime of an appliance. Such “lifetime labels” could be a star rating for a product in a category – similar to how the food star labels, or energy efficiency stars work. If the lifetime claims were independently verified, consumers could confidently decide which is more important – price or durability.

In 2020, the European Parliament voted in favour of a new policy to “develop and introduce mandatory labelling, to provide clear, immediately visible and easy-to-understand information to consumers on the estimated lifetime and repairability of a product at the time of purchase”.

If the Anko blender came clearly labelled with a one-star lifetime rating, perhaps more consumers would look beyond its everyday low price and choose a higher rated blender that’ll last much longer.

Join the campaign for durable products

Join us on our mission to reduce the mountain of broken appliances in New Zealand.

Help reduce e-waste.

We can all do our bit. Our role is to fearlessly advocate for manufacturers and retailers to make and sell better products. We’ll also provide practical, expert advice so you don’t need to replace broken appliances so often. You can help too - join Consumer today to support our work.