What we give over in good faith to use apps and online services can often be used against us in unexpected ways. Here's a good analogy about how the devices, apps and websites we use collect data that we’d rather wasn’t seen by others.

I was told a story by a mother about her son showing off his brand-new fitness tracker. He proudly displayed a chart on his computer with all his recent activity on it.

“This shows all the exercise I did,” he said, pointing to a peak in the data.

“What’s this spike here in the middle of the night?” asked his mum.

The son hurriedly shut his laptop.

“Everyone needs to consider who it is they want to protect their info

from.” - Eva Galperin

Eva Galperin - EFF director of cybersecurity.

It’s not just fitness apps with a large trove of data on our day-to-day lives. Facebook encourages us to upload photos of ourselves and our friends and to tag them with names and details. Instagram and Twitter also offer insights into our lives and the lives of our friends.

“I’m not going to tell people to stop using social media, move to a cabin in the mountains and throw their phone in the sea,” Eva Galperin, Electronic Frontier Foundation director of cybersecurity, said.

“Most users follow a principle of harm reduction in what they are currently doing.”

This means most people will take the course of action that leads to the least amount of harm for them.

“We do it subconsciously all the time; when we share, we decide what we want to be seen by our parents, workplace or school.

“Everyone needs to consider who it is they want to protect their info from.”

What do we get for the data we give up?

“How much information you want to give up is a personal choice that

reflects how much you want to access the service or buy the product,

and how much you value your personal information” - Dr Andrew Chen

How often do you think about how much information you’re giving up to companies to use their products? If a service is free, it’s likely that your personal information is how you pay for it.

“The trouble with this is that we as individuals have little understanding about the value of our information or data, so it becomes hard to know if we are getting a fair deal,” Dr Andrew Chen, Auckland University Koi Tū – Centre for Informed Futures research fellow, said.

Dr. Andrew Chen - Auckland University Koi Tū – Centre for Informed Futures research fellow.

“To make matters worse, we generally have no ability to negotiate – the vendor sets the price, and we either have to pay to participate or we get nothing."

“If you are giving a website or a company information about yourself, it’s OK to think ‘what am I getting out of this?’ in the same way you would if that website or company asked you to pay them money.”

Most of the data consumers give over is “transactional”. For example, if you buy something and have it shipped, you give over your name, address and credit card details. But you also tend to give over a lot of non-transactional data. The online shop may ask for your birthday or to track your shopping habits, or any number of other details, for seemingly altruistic reasons, like a birthday voucher.

“How much information you want to give up is a personal choice that reflects how much you want to access the service or buy the product, and how much you value your personal information,” Dr Chen said.

Are we worried about the wrong things?

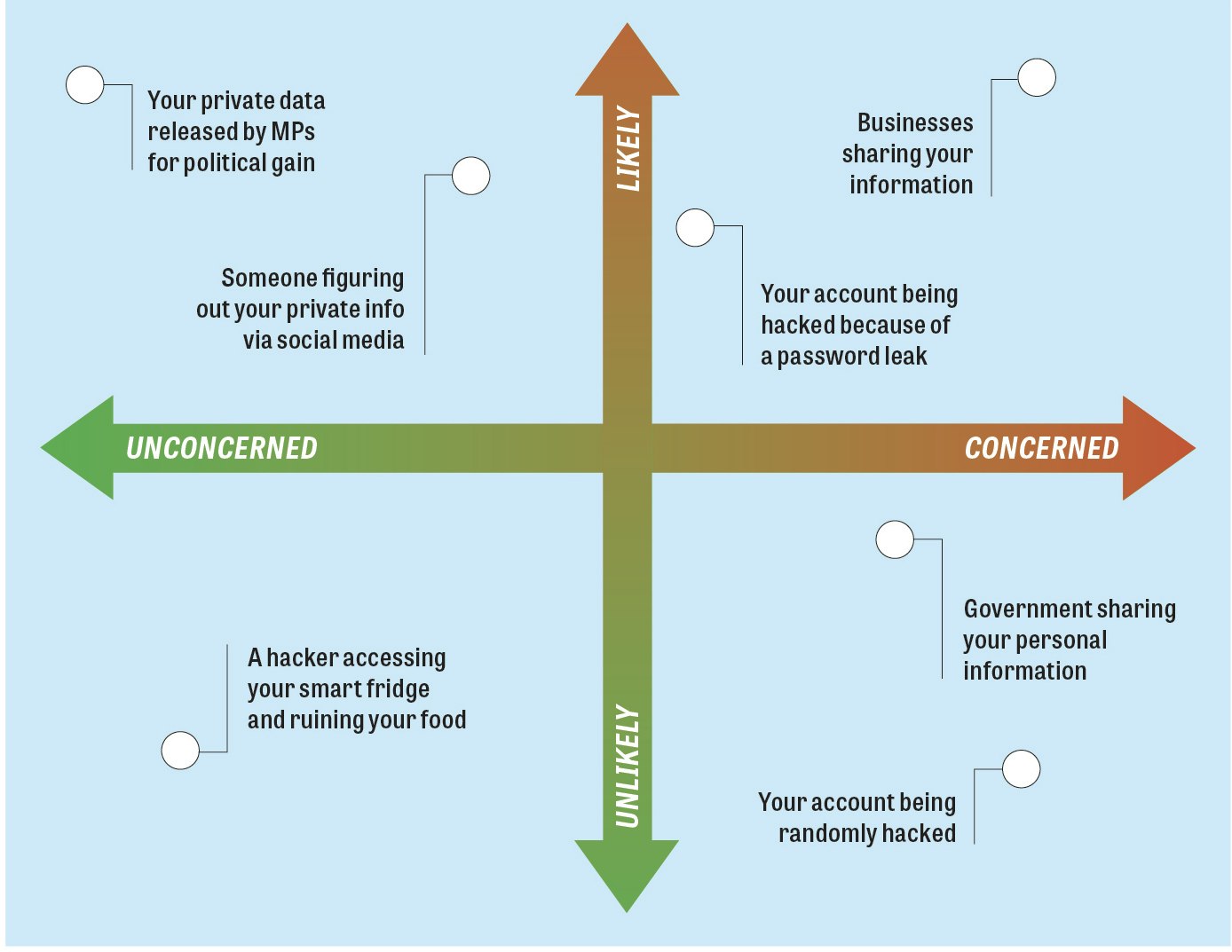

When it comes to our private data, people tend to worry about the wrong things. Like a traveller worrying about their plane crashing while driving at 130km/h to get to the airport.

What we worry about versus the likelihood it might happen (Click image for large version)

A survey by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner on attitudes to privacy found that New Zealanders worry about businesses and the government leaking their data without permission and anonymous hackers stealing their credentials. However, it’s far more likely to be a former partner, an employer or an advertiser finding and using what we share on sites like Facebook.

So, what should we worry about? Is there such a thing as a small privacy breach?

“A small breach does exist,” Galperin explained. “An example of a harmless leak might be your email and an old or useless password”.

These sorts of leaks are used for “credential stuffing”, where a malicious party gets a database containing thousands of email addresses, logins and passwords from a breached website and then uses those to try and log in to other websites.

“Of course, more leaks have a cumulative effect,” she said. “The power is not from the data gathering, it’s from correlating data from various apps and services.”

“What is safe for me or you may not be safe for those ... who are

otherwise socially at increased risk.” - Jordan Carter

One small breach might not reveal much about you, but multiple small breaches will.

“Linking up information makes user profiles more valuable for advertisers, which, for better or worse, is a huge driver of how Internet businesses make money,” Jordan Carter, InternetNZ group chief executive, said.

Jordan Carter - Internet NZ group CEO.

“Some information is highly sensitive because of what it tells people, like health records. Some information is not sensitive on its own, but when you put it together with public or leaked information, it can really harm people.”

It doesn’t take much to correlate leaked information, even if it’s anonymised, with publicly available data to pinpoint people in the community. And it’s not just you at risk.

Thinking of other people is the next level of privacy awareness. It’s slowly becoming the norm to ask “do you mind if I share this” before posting photos or other potentially revealing information online.

“Many people are in life situations where they face more risk from having their information shared”, Carter said. “What is safe for me or you may not be safe for those living with health conditions, or leaving an abusive relationship, or who are otherwise socially at increased risk.”

“Your personal information is about you, but it is also about the services you use and other people you interact with. One person deciding to share information can have big impacts on other people. For example, in the Cambridge Analytica data breach, most people affected had not downloaded the relevant app, but their friends had.”

Security is key

Keeping your information secure isn’t hard and should be part of your regular routine when online. All the experts gave the same tips, so consider these the gospel of security:

Use strong, unique passwords for every site or app.

Strong passwords – a long complex password containing letters, numbers and punctuation – are required to stop someone guessing it. Using a unique password for every account means if there is a leak, then one password doesn’t open any other account you might have. This is the “harmless leak” Eva Galperin talks about.

Use a password manager.

So you don’t have to remember all of these complex passwords, you should use a password manager. A manager means you only need to remember one strong master password to open the manager. A lot of managers will generate strong passwords too. See our guide to choosing the a password manager to pick the best one for you.

Use two-factor authentication where possible.

The advice from Galperin is to “use the highest level of two-factor authentication you are comfortable with”. This is because there are a few different two-factor (2FA) methods. The most common is where the website or app will send you a text message or email with a code. You can also use hardware-based 2FA with a USB security key – these are much more secure but require a lot more technical expertise.

Do security updates.

Apps, operating systems and devices get regular updates, and these usually include security patches. Patches are essential. They’re made using all the research from security experts to plug known gaps. As Galperin points out, “very few exploits target unknown vulnerabilities”, so it’s in your best interests to install updates the moment they’re available.

Limit what websites and apps know about you.

Signing into an app or a website for the first time, you’ll often be asked for permissions to access your data or parts of your device (for example your camera, photos or address book). Before just clicking “allow”, consider why this particular app would need this, and if you don’t think there’s a good reason, click “deny”. Similarly, if a website is asking for more of your information than it needs to provide a service, don’t give it over.

“If you do object to them collecting a piece of information, it’s helpful to send a nice polite email to them so that they know that this is a problem for some of their users,” says Dr Chen.