How will sea level rise affect you?

What you need to know about the rising oceans.

Sea level rise is here: it will hit us on the beaches, on the landing grounds, the estuaries and the streets. Like it or not, one day we’ll have to surrender.

In July, a heatwave caused wildfires and widespread melting in Greenland. The country lost 197 gigatonnes of ice that month alone – enough to raise the world’s oceans by half a millimetre.

In the coming decades, coastal and low-lying properties will be increasingly hit by storm surges and “sunny-day flooding” during king tides, as the oceans rise and extreme weather events become more frequent. The natural erosion and accretion of our coasts will alter – with the exacerbation of erosion of most concern to seafront properties.

Raumati coast beachfront resident Peter Jones is building rock wall reinforcements to protect his property, though it’s not sea level rise that worries him most. “I’m more concerned about insurance companies and councils making adverse decisions,” he said.

Fellow Kapiti beachfront property owner Gil Retter has seen storms damage his neighbours’ properties. The 70-year-old is convinced the science of sea level rise is robust, and understands coastal reinforcements should protect his home through his retirement. “I think people need to go into [coastal property ownership] with their eyes open. I don’t think it’s realistic to expect a bail out in a worse-case scenario. There’s only a certain amount councils can do in terms of defending.”

To de-muddy the waters, we asked experts how sea level rise will increasingly affect coastal regions and how New Zealand should address the issue.

Will reducing emissions help?

National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research coastal scientist Dr Rob Bell said seas have been rising in response to greenhouse gas emissions since the start of the 20th century.

“To put the brakes on, we have to cut emissions in the next few decades.”

Earth’s increasing temperature doesn’t have an instantaneous impact on the height of the oceans – there’s a delay or lag. It’s similar to how the hottest summer spells typically come weeks after the longest day with the most sunlight, though on a different scale. “Sea level rise is the last response of all the climate change effects,” Dr Bell said.

Decades-old global warming, alongside natural subsidence in some parts of the country, is responsible for the accelerating sea level rise occurring today. Similarly, an oceanic rise of another one to 1.5 metres is already “locked in” – a matter of when not if. The positive actions we take now will only pay off towards the end of the century, Dr Bell said. “To put the brakes on, we have to cut emissions in the next few decades.”

My house is pretty far from the beach. Do I have to worry?

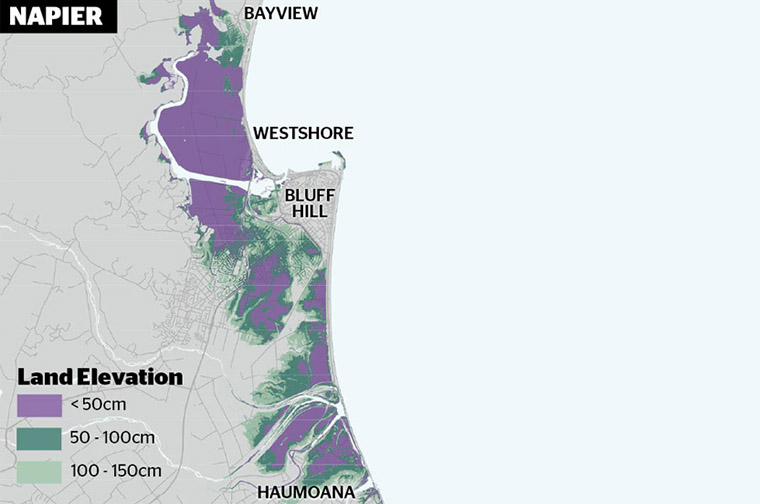

Sea level rise won’t just hit beaches, but any low-lying coastal land, Dr Bell said. “If you’re on a spit, or there’s an estuary around the back, sea level rise may not come at you from the ocean front, but behind.”

In some parts of the country, the groundwater rises and falls with the tide. With sea level rise, the water table will get higher. As this occurs, these parts will see increased surface flooding after rain, as there’s less (or no) space available for water to drain. These communities will progressively experience the type of flooding that struck south Dunedin in 2015 and 2018.

The rising seas aren’t just coming for private property. Communities face losing their beaches, roads, walkways and public facilities, such as libraries, playgrounds and town halls, on low-lying ground.

Can’t we just build sea walls?

Dr Bell said sea walls buy time – but decades only. “They’re a stop-gap measure and have a lot of limitations. A big side effect is you lose your beach,” he said.

Another is cost. The recently completed 400m sea wall at Napier’s Clifton Beach took an estimated $1.2 million to build.

With 360km of shoreline to protect, Hawke’s Bay Regional Council (alongside Napier City and Hastings District Councils) is proposing a targeted rate from 2021 to “start collecting money now to offset the future costs of expensive physical interventions”, a spokesperson for the councils said. Coastal property owners may pay a greater share than owners of inland properties, though the plan, still in its early days, requires council approval and public consultation.

Eventually, the cost of sea walls and pumping facilities might exceed the worth of the properties they’re protecting. On top of the upfront outlay is the ongoing maintenance of the infrastructure – walls take a pounding so the houses don’t.

Dr Bell said the only viable long-term solution was retiring inundated oceanfront land, a process often termed “managed retreat”.

“You can’t keep making sea walls bigger and broader – sea level rise is not going to stop. At some point, you have to bail out,” Dr Bell said. “The question becomes: how long do we want to hunker down? Sea walls should have a caveat that no future development is done on the land they’re protecting.”

Sea level rise is like aging: it’s inevitable, expensive therapies only delay it and retirement planning is essential.

Won’t my insurer come to the rescue?

Property owners may rest assured they have house insurance to cover them in a crisis. However, it’s not a golden ticket as the oceans rise.

If your property is damaged during a storm or flood, your insurer pays (up to the sum insured) to repair your home to the state it was in. The Earthquake Commission (EQC) also compensates for damage to your land – but only if it’s under or less than eight metres from your home or other buildings on the property (or under the accessway).

As insurers pay out more for climate change-related weather damage, they’ll move to recoup their losses... Eventually, properties will become uninsurable – and consequently, unsellable.

Neither will fork out for new structural defences, such as retaining walls, insurance lawyer Chris Boys said. “People need to be aware there’s going to be a shortfall.”

If you decide it’s time to move your house away from the encroaching oceans, an insurer isn’t going to pay relocation costs or purchase replacement land. Insurance covers the unforeseen, according to Insurance Council chief executive Tim Grafton. “There’s nothing unexpected or sudden about sea level rise or coastal erosion,” he said.

As insurers pay out more for climate change-related weather damage, they’ll move to recoup their losses: seafront and low-lying homes deemed high-risk will see premiums and excesses spike. These homeowners will find it harder or impossible to switch insurers. Eventually, properties will become uninsurable – and consequently, unsellable.

Will the government step in?

It’s unclear if the government will compensate homeowners forced to retreat from the seas, according to University of Otago law lecturer Dr Ben France-Hudson. There’s no law requiring them to – yet.

“However, we have a tradition in New Zealand of helping people out when they need it, though that doesn’t mean we’d necessarily help everybody, or anybody, out in the context of climate change,” Dr France-Hudson said.

Here are four different approaches:

Nature takes its course

The government (and the courts) could leave homeowners to it – both free from burdensome adaptation regulations and without any financial assistance. Such a decision would be a huge economic hit: an estimated 118,000 residential and commercial properties, with a combined value of $38 billion, are at threat from the first metre of sea level rise, according to a 2019 Deep South Science Challenge report.

With the family home comprising many people’s life savings, tens of thousands of Kiwis would be homeless and destitute. On top, they’ll be forced away from their neighbours, schools and the memories embedded in land – the yard where their children took their first steps or Fluffy McWhiskers is buried.

Restricting coastal development

Here, government puts some, or all, of the legal obligation on property owners to manage this risk.

Already, some councils are exploring planning rules to delay or soften the impact of advancing seas. For example, a Wellington waterfront development was designed with floors at least 2.1 metres above sea level, in order to receive council approval. Dunedin City Council is introducing a rule that any new residential building in specified inundation-prone areas must be relocatable.

One potential self-subsidised scheme is a targeted rate on coastal property owners...[for a] fund the house’s eventual owners would use to relocate it.

Another idea is putting time limits on coastal areas, using land covenants to require self-funded retreat. Although this would unburden rate- and taxpayers, Dr France-Hudson said this approach could leave “a hugely vulnerable community with nowhere to go”.

One potential self-subsidised scheme is a targeted rate on coastal property owners, with the cash put into a fund the house’s eventual owners would use to relocate it – sort of like KiwiSaver for coastal “retirement”.

Wait-and-see compensation

This route would see the government step in and decide the level of financial assistance after communities are forced, either by nature or authorities, to abandon the line.

However, such a system would likely be plagued by similar issues encountered by “red-zoned” properties after the 2011 Christchurch earthquakes: lengthy court cases, fights over relevant property values and “hold-outs”.

Queen’s Counsel Jack Hodder anticipates local government in particular is at risk of litigation. “There has not yet been any large damages claim in relation to failure to implement adaptation measures in New Zealand. However, it may be only a matter of time,” he said in a 2019 legal opinion for Local Government New Zealand.

Any monetary assistance may depend on how well financed and well connected each community is. “It seems to me that doing nothing requires a surprising level of bravery [from government],” Mr Hodder said.

Without clarity over what is and isn’t covered, it’s likely communities and individuals will continue to make risky decisions (such as erecting new developments on low-lying land) in the hope rate- and taxpayers will pick up the pieces.

Pre-planned compensation

Through legislation, the government predetermines what compensation – if any – coastal property owners receive when a managed retreat trigger kicks in.

Through consultation, the country would pre-emptively make the tough calls, from whether assistance covered just relocation costs or the property’s full market value to the eligibility of second homes and new developments for compensation. The funding may be dependent on homeowners paying a set fraction of costs, as occurred with the leaky home package.

University of Otago ethics lecturer Lisa Ellis said certainty allows individuals to plan for less-than-pleasant realities – for example, the surety of NZ Super allows us to prepare for old age. “When you know what your obligations are, and society’s obligations to you, it allows us to cooperate better,” she said.

Dr France-Hudson said upfront decisions were better for wider society as well: “so we don’t end up with ad-hoc responses that either don’t work or set precedents we can’t afford in the long term. Events could easily outpace us.”

Climate Change Minister James Shaw said the government isn’t working on any legislation involving compensation “although I’m not ruling that out in future”. A recently released expert panel report and internal government work will give “a better idea of the role central government should play, including issues of funding,” he said.

It’s my coastal property – what if I want to stay put?

Once erosion or the creeping waters mean a house is a risk to its occupants’ health or life, local councils are compelled to step in by law.

Before that point, a property owner’s decision to hold out will stretch the authority’s finances, as it’s tasked with piping in clean water, disposing of storm- and wastewater and providing access to the property via roads and footpaths. Floods and storm surges can damage this infrastructure, requiring repairs – a questionable use of public money if all neighbours have retreated.

Even if such realities are decades away, councils must think about them now. Under the Local Government Act, regional and territorial authorities must plan for the future and promote residents’ wellbeing without putting too heavy a burden on ratepayers.

Ms Ellis stressed the importance of affected communities having, and feeling like they have, a say in decisions. “It’s really hard for communities to have to hear these messages. You have to build trust over months and years and get everyone – scientists, council, property owners and those who don’t own property – sitting together working it through. That’s our best chance to make good decisions.”

Kapiti Coast District Council (KCDC) discovered the perils of poor community engagement when its residents took it to court over the decision to add coastal hazard zones to properties’ land information memorandum (LIM) reports. Eventually, the council backtracked.

Natasha Tod, KCDC regulatory services group manager, said councils typically prepared draft policies and then consulted with communities – but sea level rise demanded the reverse order. “We’ve got the luxury to take time to think about how we want to deal with it. It’s a conversation for everyone,” Ms Tod said. “Each response to sea level rise has a cost, including doing nothing.”

We can't do this without you.

Consumer NZ is independent and not-for-profit. We depend on the generous support of our members and donors to keep us fighting for a better deal for all New Zealanders. Donate today to support our work.

Member comments

Get access to comment