By Gemma Rasmussen

Head of Research and Advocacy | Tumuaki Rangahau, Taunakitanga

Many New Zealanders are fretting about their grocery bill, but will it go down any time soon?

Arriving in New Zealand

Nearly three years ago, I arrived in New Zealand after a decade overseas. During the heights of Covid uncertainty, I slipped into the country from Sydney, two days before managed isolation started. We packed in a hurry with two suitcases, and two small children in tow. My partner and I hunkered down in a little house in a remote coastal town to complete our two weeks of self-isolation, with my mum arranging a grocery shop for us on arrival to help get us through the first week.

Inquiring about the price of the shop so I could transfer some money, my mother casually told me it was $400. I was confused – perhaps she had gone a bit over the top due to excitement of her only daughter re-entering the country?

Going through the shopping bags, I found she had made practical choices: loaves of bread, leafy green vegetables, packets of pasta, rice, spices, a few cuts of meat, a block of chocolate. There was nothing extravagant. It was just enough to get us through the week, but the price left me staggered.

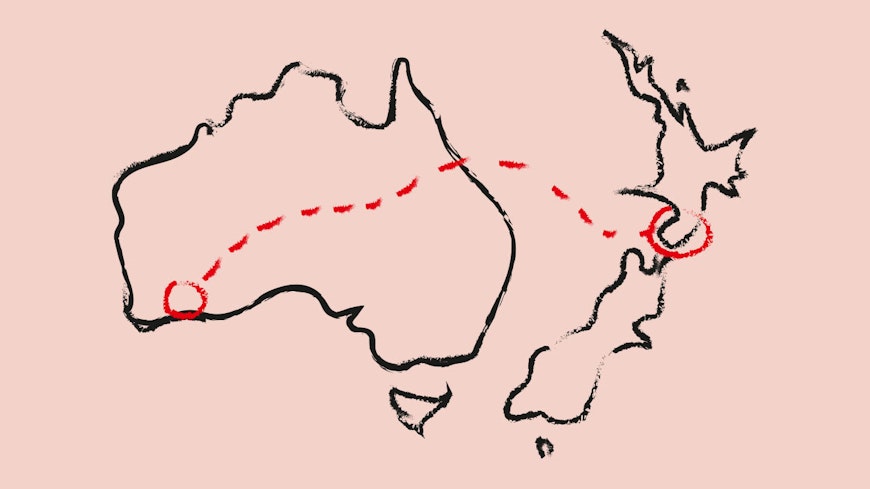

Living in Sydney, we enjoyed shopping at Coles, Woolworths, Aldi (a discount German supermarket chain) and Harris Farms (a local supermarket chain). Four major supermarkets were all located within a 10-minute drive of our house. We could shop by special and pop into one supermarket for its competitive pricing on produce, another for bargain basement-priced German chocolate, and then swing past the next for well-priced meat.

There was also a local produce market we frequented on weekends, so choice on where to buy food was abundant. Each week, we’d spend around $250 on our groceries, and it covered everything we needed. I thought this was normal. But it was evident that I’d been away from New Zealand for too long. Many Covid returnees lamented the same thing, highlighting how jarring the cost of food was.

The supermarket duopoly

When it was announced at the end of 2020 that there would be a market study into supermarkets, there was a healthy mix of excitement, scepticism and interest from the public. We are all directly affected and there are so many factors that go into pricing food, it can be hard to know what a fair and competitive price is.

Supermarkets are complex beasts. Combine that with the fact our duopoly holds at least an 80% share of the market, and it was fair to question whether the supermarkets were doing good by New Zealanders. There were several concerns: a lack of transparency about pricing, reports from suppliers of poor treatment, and how incredibly hard it is for new competitors to enter the market.

When the final report into the $22 billion sector was delivered, it established that competition in the industry was muted, and that competitors who wanted to enter or expand in the market were up against significant challenges. It was also established that the supermarkets were making about $430 million a year in excess profits – a figure that saw public trust in the supermarkets sharply plummet.

With the lack of competition firmly established and profits sitting at questionable heights, there was no apology or a sheepish admission from the supermarkets, but promises to co-operate with the Government to bolster competition.

An action plan was set with the introduction of the Grocery Industry Competition Bill. This established a Grocery Commissioner to referee the sector, meaning a closer eye would be kept on the major players, as well as annual reviews to ensure competition is actually healthy in the sector. The bill will also enable collective bargaining and it will implement a Grocery Supply Code to protect suppliers from unfair contract terms. This all sounds like progress, and we’ll see this come into effect in the middle of this year.

Factors affecting the food prices

Other issues have been brewing, causing pain at the checkout. There are global pressures on food supply and pricing, including shortages due to erratic weather; increases in production costs due to rising costs of fertiliser, fuel, packaging and the like; and a labour shortage and an uptick in wages.

The question for shoppers is: Are the prices you’re paying for food fair and competitive, and are there instances when the supermarkets are using cost-of-living pressures as a smokescreen to jack their prices?

When you pick an item off the shelf, there are so many factors that go into that pricing, it can be hard to know whether you’re paying a fair and accurate price. Whether you’re an average shopper or a seasoned economist, it’s near impossible to break down the pricing of any food item on the shop floor.

Supermarket pricing tactics

Identifying a fair price can be made all the harder if you’re constantly being pressured into thinking you’re nabbing a bargain. A trip down the aisles of New World, Pak’nSave or Countdown can be a confusing experience, with ‘specials’ plastered from wall to wall. If you’re to believe the supermarket signs, there are deals to be had.

Extra low, multi-buy, great price, everyday low, club card price – it’s all laid out. The supermarkets understand the persuasiveness of an appealing special, which can leave the shopper vulnerable if the sale is not genuine. A recent trip down the aisles of my local New World found a sale ratio of roughly one to six. That’s a lot of discounted pricing to process as you make your way around the shelves.

When you reach the checkout and watch your total shop price reach dizzying heights, it can be a jarring disconnection from the shopping experience you’ve just had, where the aisles have been screaming at you about and ‘value’ and ‘super saver’ and all the deals you’ve been nabbing.

Concern around food costs

Fran Mackay, a New Zealander living in Singapore, is used to expensive food. Singapore ranks as one of the costliest cities in the world, with food prices being particularly high. That said, New Zealand grocery bills are still shocking to her.

“You know something is weird when you’re used to paying exorbitant amounts of money for food in Singapore and somehow New Zealand is outstripping those costs,” Fran said.

“Whenever we come home, the food costs are jolting. Mainland butter, on Singaporean grocery shelves, is less expensive than in New Zealand. It’s enough to raise an eyebrow when you know butter that’s flown on a plane is cheaper than on local shores.”

For Laura Pevreal, a mother of two from Cambridge, the price of food has meant lifestyle adjustments.

“We used to do a one-stop shop at the supermarket but we’re becoming more inventive in the ways we source and make our food, because the prices are just too high,” Laura said.

“We’re growing vegetables where we can, and I’ll make things like bread or homemade muesli bars, and broths and stocks with leftovers, because store bought is too expensive for us.

“With us both working, with two kids, all the additional time to source and prep food is tiring. We’re exhausted, but we are making those adjustments to save money.”

Research from Consumer NZ has found that people are preparing themselves to spend more on groceries. In June 2021, 24% of people expected they’d need to shell out more on food in upcoming months. Fast forward a year and in June 2022, 47% of people were preparing to set aside more of their budget for food.

The cost of food is now listed as the second highest financial concern for New Zealanders after housing, compared with a year ago, when it was ranked eighth. Many households are asking the dreaded question: How much higher can food prices go? Statistics NZ reported the highest annual jump in 13 years in 2022, as inflationary pressures continue to bubble along.

The cost of household essentials such as dairy, eggs and vegetables have been central to the price hikes.

According to economist Shamubeel Eaqub, these food hikes have been unprecedented and they could continue to climb this year.

“If you look through the history of food pricing in New Zealand, it has gone up and down a bit but not by these standards,” he said.

“In the last year there was a 10% increase, which is unlike anything we’ve ever seen. Incomes certainly don’t change by that much in a year, so it’s a difficult thing for people to absorb those cost increases into their budget.”

“In the next year we should be bracing for more food increases, not as severe as we’ve seen but they could be in the order of 5%. As a nation, our cost of food is high and we’re very much reliant on the global market due to the amount of food we import, the fact we export a lot of our domestic food, coupled with our weakening dollar and food price inflation.

“Compared to a market like the United States where a higher proportion of food is grown and then provided to the domestic market, as a nation we are not immune to what is playing out globally, which can lead to volatile pricing.”

When grilled on whether we can rely on the major supermarkets to dish up fair pricing in 2023, Shamubeel believes the answer lies ‘in the profit margins’.

“If you look at the profit levels during 2020/2021, they were very healthy. The major supermarkets essentially stopped specials and promotions during Covid lockdowns, when people had nowhere else to shop.

“Until there is another player, I don’t think we’re going to see a dramatic change in the supermarket sector,” he said.

“We know there’s a lot of scrutiny and pressure that the supermarkets are under, and sunlight is the best disinfectant, but it remains to be seen how this will play out.”

The year ahead looks to be bumpy, with interest rates climbing and consumer confidence dipping. When it comes to cheaper prices at the checkout in 2023, we shouldn’t hold our breath. The supermarkets know that they are being watched, and the Government has made some bold statements on action to be taken if the duopoly refuses to play ball, including fines or even being forced to sell off stores to new players.

However it plays out, fundamental and positive change in the sector will take years to come to fruition. And for most households, the choices on where to buy groceries remains limited. For shoppers around the country, it’s looking like another year of very expensive groceries is on the cards. Unfortunately, pre-pandemic pricing won’t be rolling around any time soon.

Back our fight for honest grocery prices

With your support, we can build a safer, fairer and more equitable future for New Zealanders. Join today to help us hold supermarkets to account.