By Chris Schulz

Investigative Journalist | Kaipūrongo Whakatewhatewha

Fans are angry about surge-pricing tactics being used to sell concert tickets at higher prices. Consumer tries to unpack the “in demand” epidemic.

When Liz* logged onto Ticketmaster recently to buy a concert ticket, she found the prices confusing.

Her niece, Gabby*, wanted a ticket to see SZA, an American R&B star who recently performed several shows at Auckland's Spark Arena.

Gabby would be at school when tickets went on sale, so Liz offered to get her a ticket for SZA's second show, on 16 April.

In the ticket pre-sales, which Gabby had missed, the cost of a general admission floor ticket was $249.90, plus fees.

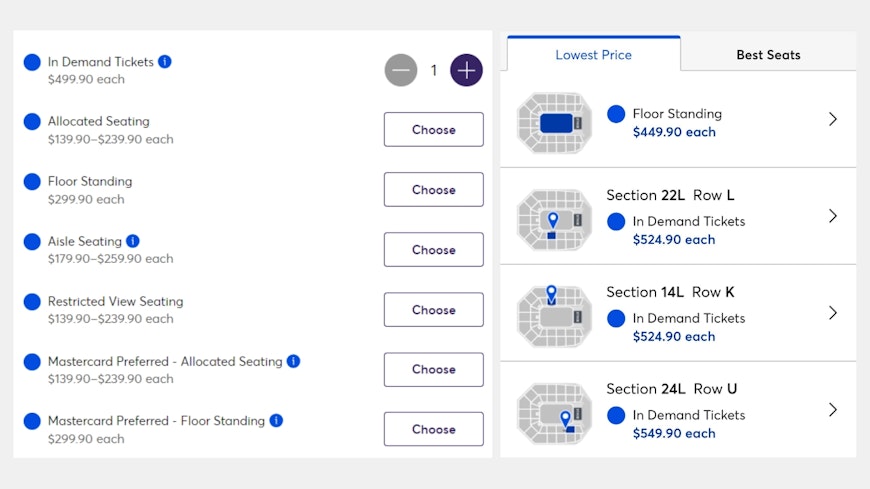

But when tickets were released to the general public a few days later, Liz could only find a general admission ticket for $424.90. Other tickets were priced even higher, as much as $549.90.

Because Gabby was at school, Liz was unable to check whether she still wanted the ticket at that price. "It's her first concert and she'd only asked for one ticket," she says, admitting, "I was in a hurry."

So, Liz went ahead and purchased the ticket, thinking she could always sell it for the same price if Gabby didn't want it or couldn't afford it.

Although she didn't realise it at the time, Liz had purchased a ticket at "in demand" prices.

Ticketmaster sells these tickets at what it calls "market driven prices", which are often much higher than the cost of a normal ticket.

A few weeks after her purchase, a third SZA show was announced for 13 April. Demand for that concert was lower, and tickets in the same section were readily available for $249.90.

Liz felt ripped off. Not only had she paid nearly $200 more for her niece's ticket, confirmation of a third show meant it would now be much more difficult to resell her ticket at that higher "in demand" price.

"It seems unfair ... to have such a wide variation in pricing for a 16-year-old attending her first concert," she says.

What is an 'in demand' concert ticket?

In her desire to help her niece, Liz had been caught out by surge-pricing, a marketing technique otherwise known as "dynamic pricing," and a practice being used with increasing regularity.

Surge pricing is why a taxi fare or Uber costs more from the airport or during the evening rush, and why flights and hotels raise their prices during peak periods like school and public holidays.

Lately, though, it's also being used by other industries: some London pubs are charging more for a pint at peak times, while fast food outlets have mooted doing the same thing with sales of burgers and fries.

Now, many major event and ticketing agencies are doing it too, including Ticketmaster and Ticketek. That means a select number of tickets for many shows are being sold at “in demand” prices.

“In Demand Tickets are tickets offering sought after views and seats from Ticketmaster,” says Ticketmaster. “The goal is to give fans fair and safe access to the best tickets while enabling artists and other people involved in staging live events to price tickets closer to their true market value.”

Other artists selling in demand tickets to upcoming shows in New Zealand include Twenty One Pilots (with tickets as high as $299.80), Pearl Jam ($469.90, renamed as “PJ Premium” tickets) and Chris Stapleton ($499.90). Yet those artists also have tickets for sale at the same shows at much lower prices.

Dr Sommer Kapitan , associate professor of marketing at the Auckland University of Technology, believes this is a sales tactic consumers need to be wary of. "It is all about increasing revenue margins," she says. "If you see it, and people are buying it, that means it's working."

She believes marketing techniques like surge pricing create a feeling of FOMO (fear of missing out), exploiting consumers who will pay to attend an event no matter what the cost.

"Consumers say, 'I still want to have that experience, and I'm willing to pay for that,’” she says. “There's a sense of competition, especially for concert tickets, especially for your favourite show, or a nostalgic show that you're really interested in going to.”

Social media has helped drive demand for exclusive experiences, Kapitan says, so she isn’t surprised that event companies like Ticketmaster are using surge-pricing tactics more often.

"If the market allows for it, they're going to keep doing it," she says. She warns those prices could get higher than they already are. “They can take it quite far.”

What are consumers’ rights?

Liz approached Ticketmaster to ask if a mistake had been made with the price of her ticket.

She was told ticket prices can rise depending on demand. “The tickets you booked were purchased with the agreement to pay the ticket price set at the time of the booking".

When approached for comment, Ticketmaster pointed Consumer to the frequently asked questions section of its website dedicated to “in demand” tickets.

Consumer understands tickets aren’t priced by Ticketmaster; instead, the cost is set by artists, promoters or event organisers.

Live Nation, the promoter of SZA’s New Zealand shows, also owns Ticketmaster.

Ian Caplin, a business specialist at the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, says under the Fair Trading Act advertised prices, "must be genuine, and must not contain extra costs you weren't told about".

Businesses are free to set their own prices for a product or service, and increasing prices because of demand isn't illegal in New Zealand.

"Surge pricing is not seen as misleading or deceptive, as long as the advertised price is the same as the actual price (or lower)," Caplin says.

Unfortunately for Liz, announcing another concert with lower prices also doesn't breach the Fair Trading Act.

"In this instance, if the original price advertised was $450, which is what the person paid, only to find a future price lower than what they paid, even if it’s for the same product/event, there is no breach of the FTA," Caplin says.

Can you avoid surge pricing?

While consumers can avoid surge-pricing for travel by booking outside peak times, that's a harder thing to do when it comes to a one-off concert by an artist you love.

If you're a major fan, it's worth signing up to an artist’s’ fan club. Recently, pre-sales for shows by Twenty One Pilots and Pearl Jam were available to those who had registered, helping fans avoid surge-pricing tactics.

Some artists, including Neil Young, have spoken to reporters or lashed out on social media against surge-pricing tactics when it comes to concerts. The Cure’s Robert Smith called it “a greedy scam”.

Yet Kapitan says the only way to make it stop is for fans to stop buying concert tickets. “It's only through collective action or regulation that any individual consumer has any power,” she says.

She admits that’s unlikely to happen. “If people don't want it they can boycott it, but then the people who do want it will buy it.”

Gabby kept the ticket Liz bought her, paying for it with the help of her dad.

But Liz says the experience means she's unlikely to use Ticketmaster again.

"It didn't make me feel good at all,” she says. “I felt really disappointed for my niece and ripped off when we realised that they were selling tickets ... much cheaper.

"I don't think we would buy from Ticketmaster again unless we really, really wanted to see the show."

*Last names withheld to protect identities.

It's time to stop ticket reselling rip-offs

We regularly receive complaints about ticket resellers and their hugely inflated prices. But sky-high markups are not the only problem with these ticket resale sites.