By Belinda Castles

Researcher | Kairangahau

We know eating less processed food is better for our health but research is mounting that the degree of processing also plays a part. Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are being linked to a number of illnesses, such as heart disease, cancer and stroke.

What are UPFs?

The most well-known definition of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) is from the NOVA classification framework, developed by Brazilian researchers. NOVA classifies foods into four groups according to the extent and purpose of processing.

Unprocessed or minimally processed foods: These have undergone no or minimal processing and have no added oils, fats, sugar, salt or other ingredients. Examples include rice, rolled oats, meat, legumes, frozen fruit and frozen vegetables.

Processed culinary ingredients: The processing creates products that can be used to prepare, season and cook unprocessed or minimally processed foods. Examples include butter, vegetable oils, sugar, honey and salt.

Processed foods: Products made from natural or minimally processed foods with the addition of culinary ingredients such as oil, sugar or salt. Examples include cheese, peanut butter, plain canned fish, canned fruit and canned vegetables.

Ultra-processed foods: Ready-to-eat products with little to no whole foods, and they have added sugar, salt, fats, additives and preservatives. These foods often contain ingredients you wouldn’t cook with at home or have in your pantry, such as colours and emulsifiers. Another trait of UPFs is the processing they go through. These include hydrogenation and extrusion – not tasks you’d do in your home kitchen. Examples include biscuits, crackers, most packaged breads, chips, chicken nuggets and ready-to-eat meals.

UPFs appeal for a number of reasons. They are convenient (typically ready to eat or heat), tasty (so they’re easy to overeat) and are often heavily marketed.

Aotearoa’s food supply is stacked with them. A University of Auckland report from 2019, The State of the Food Supply, found that 69% of the 13,000+ packaged foods in the survey were categorised as ultra-processed. In many product categories, more than 85% of products were ultra-processed, including snack foods, bread products, meat alternatives, and sauces and dressings.

It's a similar story across the ditch. The George Institute for Global Health’s 2022 State of the Food Supply report found 80% or more of the product range of 12 of the top 20 food manufacturers in Australia was ultra-processed.

Are UPFs bad for you?

UPFs are often high in energy and unhealthy nutrients such as sodium and sugar, and low in beneficial nutrients like fibre and protein. They contain little or no whole foods and often have additives such as sweeteners, colours and flavours. They are easy to overeat and can displace healthier, less-processed options.

There’s growing evidence that eating lots of UPFs is bad for your health. Strong associations have been found between high intake and increased health risks, such as being overweight and having obesity, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, breast cancer and depression.

A 2023 UK study published in The Lancet found that higher intakes of UPFs may be associated with a greater risk of developing cancer. For every 10% increase in UPF intake, there was a 2% increase in the incidence of overall cancer, and a 19% increase for ovarian cancer in women. The study also found an association with dying from cancer, in particular breast and ovarian cancer.

There are also emerging concerns that UPFs are addictive. An opinion published in Addiction in 2022 concluded that highly processed foods can be considered addictive based on criteria such as triggering strong urges or cravings, causing mood-altering effects, and causing controlled or compulsive use.

How much are we eating?

Globally, UPF intake is increasing. In the USA and UK, it’s estimated nearly 60% of energy intake comes from UPFs. Australia isn’t far behind, on 42%. Brazil (where cutting back on ultra-processed foods is recommended in dietary guidelines) leads the way, with only 20% of kilojoules coming from UPFs.

We don’t have recent nutrition survey data for New Zealand. But a 2021 University of Otago study published in the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics looked at the UPF intake in young children at 12, 24 and 60 months. The study found UPFs contributed 45%, 42% and 51% of energy intakes to the diets at 12, 24 and 60 months. Most frequently eaten foods were bread, yoghurt, crackers, whole wheat breakfast cereals, sausages and muesli bars.

Is all processed food bad?

Food processing doesn’t always equal unhealthy. Some processes have benefits such as freezing, fermentation and pasteurisation. But generally, the further a food gets from its original state, the less healthy it is. But when it comes to UPFs and how they are classified, it’s not always straightforward.

Dr Sally Mackay is Health Coalition Aotearoa’s Food Policy Expert Panel co-chair and lead author of The State of the Food Supply report. She said one of the main issues with the NOVA system is that the degree of processing isn’t always a direct link with nutrition. Some core foods that form the basis of a healthy diet, such as many bread and breakfast cereals, are classified as UPFs.

“People are short of time so there’s always going to be a need for convenience foods that are ultra-processed,” Dr Mackay said.

“But there’s a big difference between a cereal like wheat biscuits and sugary Coco Pops. There needs to be further classification of the system – UPFs that are core, everyday foods versus those that are discretionary and shouldn’t be eaten often.”

University of Otago’s head of the department of medicine Professor Rachael Taylor agrees.

“The concept of choosing foods based on the level of processing is a good but imperfect one. One of the main issues is that different people classify the same foods quite differently. This lack of consistency means we should be cautious when we interpret data relating to UPFs.”

What needs to change?

A poor diet is a leading cause of illness and early death in New Zealand. Public health agencies, including Health Coalition Aotearoa (of which Consumer NZ is a member) believe there are a number of initiatives that could improve the quality of the food supply and help consumers make healthier choices about the processed foods they are eating.

Make the Health Star Rating (HSR) mandatory. HSRs give consumers at-a-glance information about a packaged food’s overall nutritional value.

Regulate food marketing to children. There’s evidence unhealthy food marketing to children is contributing to our obesity epidemic. Usually the foods marketed are ultra-processed and high in energy, saturated fat, sugar and sodium.

Mandate healthy food policies in schools and early childhood learning centres.

Introduce a tax on sugary drinks. Sugary drinks are the main source of sugars consumed by Kiwi children and young people. They’re associated with tooth decay and weight gain.

Initiate Government-led reformulation targets for sugar, saturated fat and sodium for key food groups. This will increase the healthiness of the food supply.

Looking at UPFs

In general, the more processed a product, the less healthy it is. We look at six foods, from whole to ultra-processed, to see how they stack up in the nutrition stakes.

Tomatoes

Tomatoes are rich in vitamins A and C, niacin and the antioxidant lycopene. Canned tomatoes usually have their skin removed and are either whole, chopped or pureed. They’re often 100% tomatoes (so are nutritionally similar to fresh tomatoes) but some brands contain added salt.

Sun-dried tomatoes have had their water removed. Compared with fresh tomatoes, they have a higher natural sugar content and more kilojoules. Some brands are packaged in oil and have salt or sugar added. Delmaine Sundried Tomatoes have a whopping 1470mg of sodium per 100g.

Tomato sauce’s main ingredient is usually tomato concentrate. But sugar and salt are often high up the ingredients list. Wattie’s Tomato Sauce is nearly 30% sugar and has 935mg of sodium per 100g.

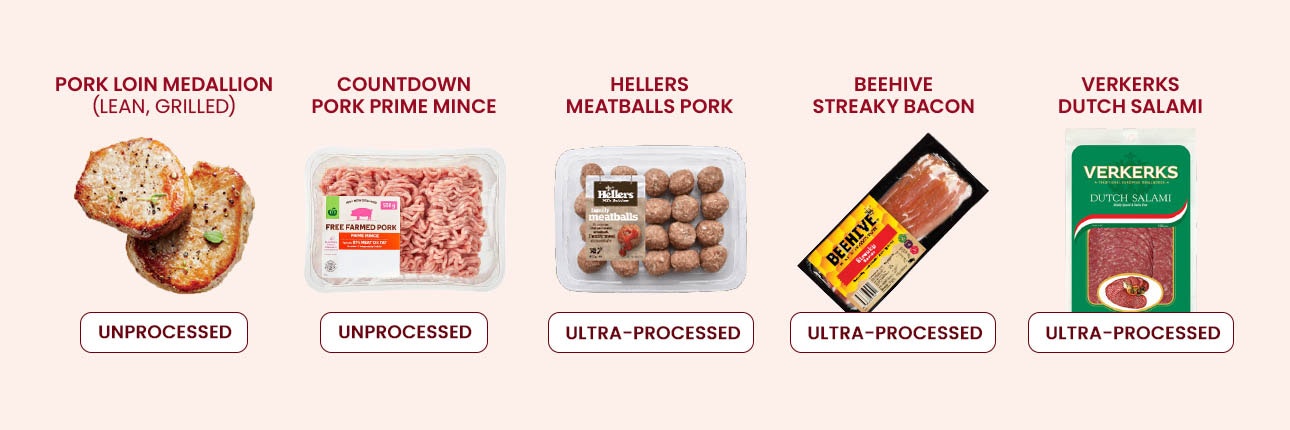

Pork

Pork is a good source of protein and nutrients such as iron and zinc. Pork mince is made by mincing the meat and store-bought mince is usually 100% meat.

Store-bought meatballs often have a range of products added such as salt, starch, spices and preservatives, so are higher in sodium than pork mince. Hellers Pork Meatballs have 587mg per 100g.

But when pork is processed into bacon and salami, there’s a big jump in saturated fat and sodium. Beehive Streaky Bacon is 11.4% saturated fat and has 890mg of sodium per 100g. Verkerks Dutch Salami tips the sodium scales with 1673mg per 100g. Eating processed meat is also linked to an increased risk of bowel cancer and heart disease.

Potatoes

The humble spud is a good source of nutrients, including fibre. While store-bought oven fries can be an OK choice, they aren’t all created equal. Countdown French Fries (96% potato) only have 60mg of sodium compared with McCain Pub Style Beer Batter Fries Steak Cut (86% potato) with 260mg.

Sadly, potato chips can’t count toward your 5+ a day. Per 100g, Bluebird Originals Chicken Chips have 2240 kilojoules and 788mg of sodium.

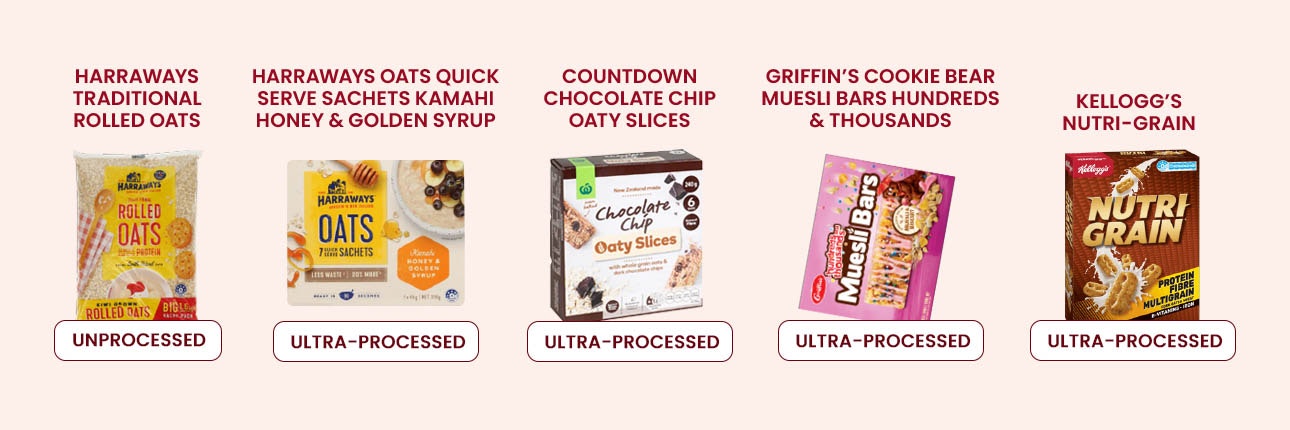

Oats

Whether chopped up (steel-cut) or rolled thin (quick-cook), oats are high in fibre and packed with vitamins and minerals. Oats are also rich in beta-glucan, a soluble fibre that helps keep blood cholesterol down. They are a healthy choice as long as you don’t add lashings of brown sugar.

But be wary of single-serve flavoured sachets. Many provide a sizeable sugar hit. Harraways Oat Sachets Kamahi Honey & Golden Syrup contain 25% sugar – that’s on par with Kellogg’s Nutri-Grain (24%).

Muesli bars with oats are still a source of fibre and other nutrients. But their nutritional value takes a dive because of the many added sugars used to make them stick together. Griffin’s Cookie Bear Muesli Bars Hundreds & Thousands (29% sugar) includes glucose syrup, icing sugar, invert syrup, brown sugar and honey in the ingredients list.

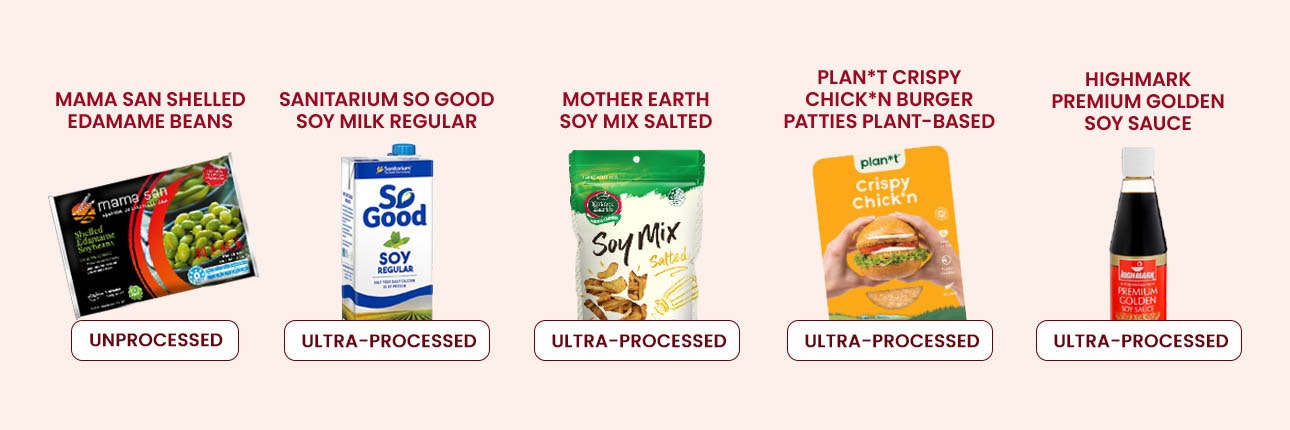

Soybeans

Soybeans (also called edamame beans) can be bought fresh or frozen and are a good source of fibre and other nutrients.

Soy milk is made from whole soybeans or soy protein. It’s the most nutritionally comparable milk alternative to cow’s milk. Most soy milks are fortified with calcium but watch out for sweetened varieties. When we surveyed plant milks in April, we found some had added sugars.

Soy is also a common ingredient in many unhealthy, ultra-processed snacks in the guise of soy protein, soy flour or soybean solids. Mother Earth Soy Mix Salted snacks contain 2200 kilojoules per 100g and are high in sodium (670mg).

Soy is also found in meat alternatives, such as Plant Crispy Chickn Burger Patties. These ultra-processed, plant-based convenience foods have lengthy ingredient lists and aren’t the same as eating whole plant foods we should be eating more of, like legumes.

Soy sauce takes the award for the saltiest product. Although only used in small quantities, it contains 6780mg of sodium per 100g. One 30ml serving contains 2034mg – that’s more than the Ministry of Health’s recommended daily upper limit of 2000mg.

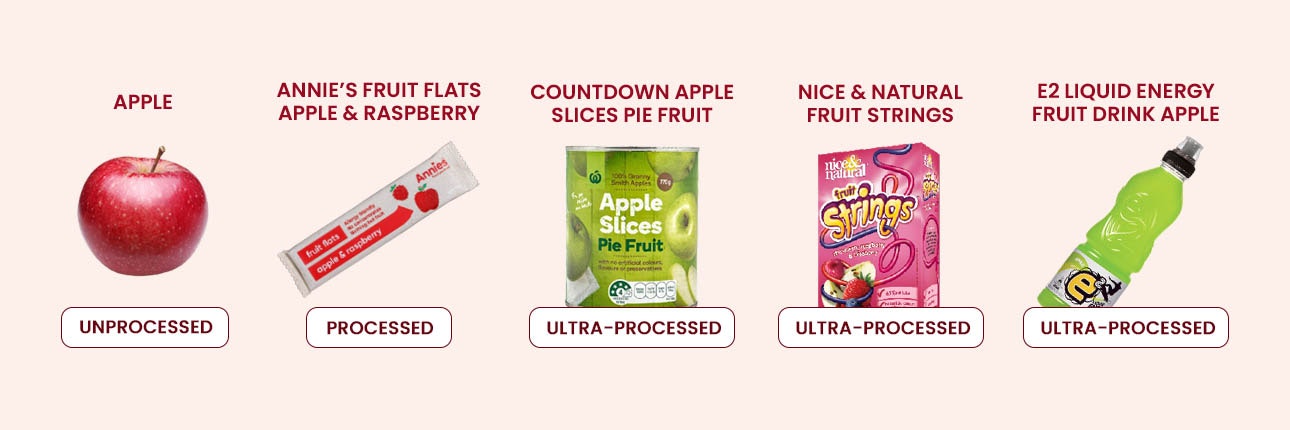

Apples

An apple a day keeps the doctor away but not when it’s added as a puree, concentrate or juice.

Annie’s Fruit Flats Apple & Raspberry contain nearly 60% sugar. Although the sugar comes from fruit puree, it’s not the same as eating whole fruit. Dried fruit is high in kilojoules and can stick to teeth, therefore increasing the risk of tooth decay.

Beware of products making ‘fruit juice’ claims. Nice & Natural Fruit Strings are made with 65% fruit juice (the majority is apple), but with their added glucose syrup and sugar, they are a poor substitute for a piece of fruit.

It’s a similar story for fruit drinks. ‘Fruit drinks’ aren’t ‘fruit juice’. They only have to contain a minimum 5% fruit content. For example, e2 Liquid Energy Fruit Drink Apple only contains 5% apple juice from concentrate. Its main ingredient (after water) is sugar.

Canned fruit would usually be classified as processed, but Countdown Apple Slices Pie Fruit also contains salt, citric acid and a firming agent.

DATA SOURCE: Information from product packaging or The Concise New Zealand Food Composition Tables 14th Edition 2021.