By Paul Smith

Former Head of Test | Kaiwhakahaere Whakamātautau

Our system is broken.

Most faulty small appliances don’t get a second life and are simply thrown away by retailers and manufacturers or, at best, get recycled. We throw out more than 20kg of e-waste per person per year, about 100,000 tonnes in total. There are very few local repairers, because most small appliances are too hard to repair – it’s just not worth it.

If you’re shopping for a new small appliance, like a microwave or food mixer, it’s unlikely you’ve considered a used one because, compared to buying new, the second-hand experience feels like a third-class option. You can buy refurbished appliances, but it takes a lot of effort on your part. There are a few outlet stores that carry stock from the few brands that allow resale of their used products, but your choice is very limited. You could shop at an op shop, on TradeMe, or roll the dice with Facebook Marketplace, but you’ll get no consumer protection there.

There’s no way for you to really know which new appliance is more durable or repairable, and which is likely to get chucked away when it fails too soon. Many manufacturers don’t even want their appliances to be repaired and resold – they think it devalues their brand. Many of them tout grand sustainability claims, but you have no way of telling if they walk the walk, or if it’s just greenwash.

“I think it's incumbent on all of us to say, ‘what kind of economy do we want?’ Do we want a main street where we have local people [who] know how to fix and maintain our things? Or do we want a factory assembly line where we manufacture stuff in Asia, we dump it here, use it for however long it works, and then there's no maintenance plan for it?” - Kyle Wiens, chief executive of iFixit

Project Mixer: uncovering the problem

After exploring how this part of the industry works, I’m disappointed but hopeful that it can change for the better. I’ve seen some dedicated people and businesses trying very hard to make it happen. But some parts of it need a push – not least the manufacturers who actively prevent their products being resold.

Here’s a recap of Project Mixer – how we discovered the ‘cut and chuck’:

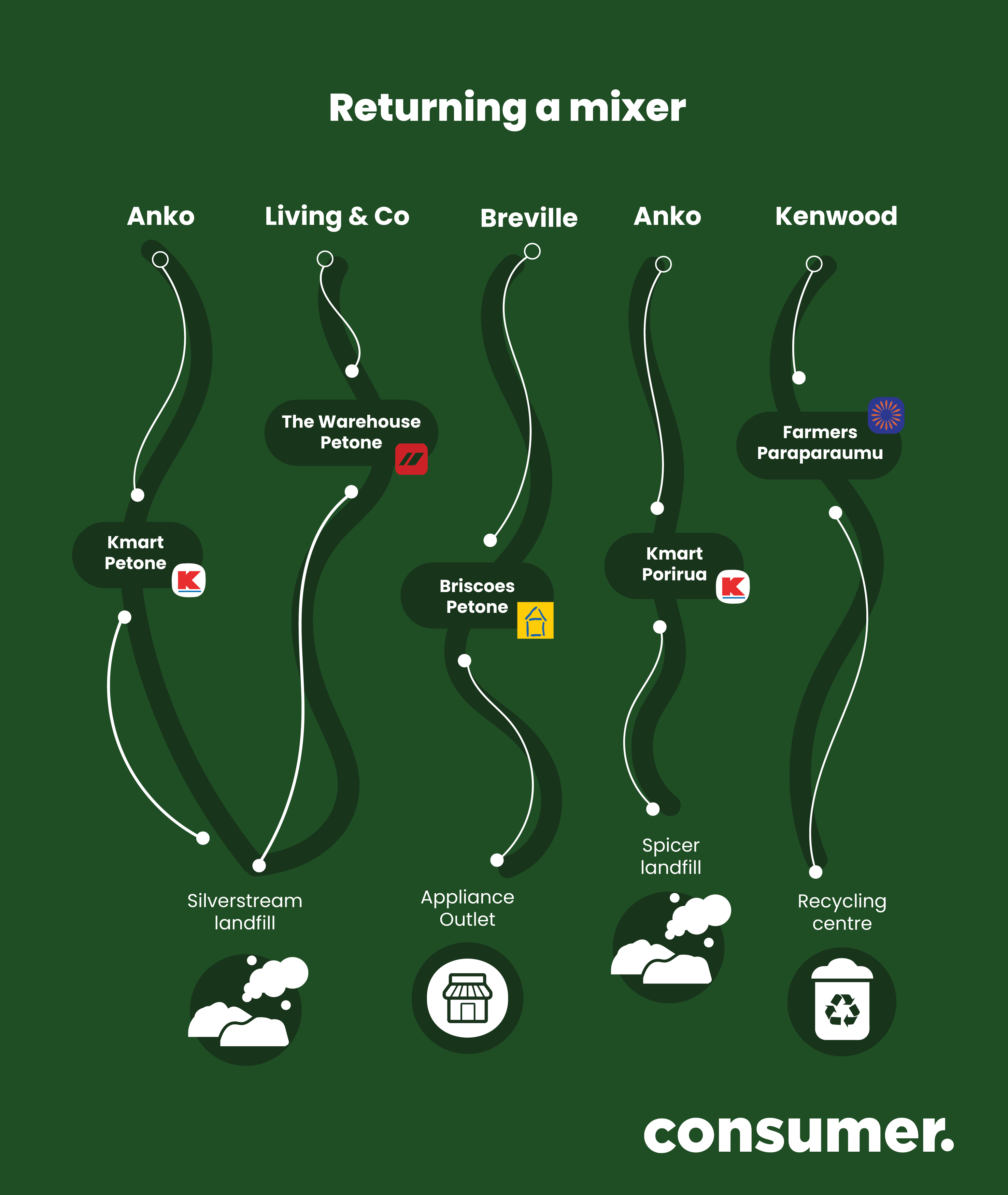

We hid GPS trackers in several benchtop food mixers. We created an easy-to-repair fault, returned them to the stores, then tracked their journeys. After three months in the wild, we accounted for all of them:

Living & Co (The Warehouse), $79. Buried in Silverstream landfill.

Anko (Kmart), $75. Signal lost in transit, assumed buried in Silverstream landfill.

Anko v2 (Kmart), $75. Buried in Spicer landfill.

Breville (Briscoes), $450. Repaired and sold, refurbished, by Appliance Outlet.

Kenwood (Farmers), $740. Recycled by Computer Recycling.

If you haven’t heard our podcast, you should start by listening to that, then reading about our journey to find out how the appliances ended up where they did.

The cut and chuck

'Cut and chuck' is a cute phrase to describe the worst behaviour in this broken system.

You buy a kettle (or any small appliance). But it doesn’t work very well, so you take it back to the store. The store gives you a credit or refund and takes the slightly used and unwanted kettle off your hands.

The store has met its responsibilities under the Consumer Guarantees Act (CGA) and kept you, its customer, happy. It gets a credit from the manufacturer for the return and hands over the used kettle.

But what to do with that old appliance? There’s no value in refurbishing it, so the manufacturer expends minimum effort and cost … it instructs the store to remove the plug (the cut) and throw it out (the chuck).

If we’re lucky, the chuck might be to a company which will recycle the kettle as e-waste, but it’s also likely it’ll end up buried in the nearest landfill.

It's all such a tremendous and unnecessary waste.

Not our problem

A manufacturer’s business is to sell new appliances. It doesn’t want the inconvenience of dealing with those appliances when they are unwanted and broken. Manufacturers have two options that absolve them of responsibility: they throw them into landfill or they pay someone else to deal with them.

“Someone else” includes the businesses which got our mixers: Appliance Outlet and Computer Recycling. They do good things. They are paid by the manufacturer for shouldering its end-of-life responsibility. They eke out any remaining value by repairing and reselling, dismantling for parts, or recycling the appliance’s materials.

Their work is labour-intensive, made less viable because the manufacturers don’t care what happens to the appliances (it’d be easier if we just threw them away). Having given up their responsibility, manufacturers have no incentive to make appliances that are easier to repair or recycle.

For the lowest-cost appliances, there’s no “someone else” willing to take responsibility for them. They simply get thrown away.

Making it everyone’s problem

Many manufacturers won’t change unless they have to; their businesses are built to sell new products. One of the cheaper brands told us that directly – they won’t do anything until the Government points them in the right direction. It’s a cop-out for sure (throwing appliances into landfill is never going to be the right direction), but it means legislation is important to get them moving.

We think three pieces of legislation are needed to fix our e-waste problem:

Product stewardship

Product stewardship ensures those who make and sell products are responsible for what happens to those products at the end of their life. Every electrical appliance or electronic device placed on sale attracts a stewardship fee. In the simplest incarnation of a scheme, the fee is used to pay for recycling. However, if the scheme is set up well, it also supports repair and refurbishment activities to keep products in use for longer.

The Right to Repair

A Right to Repair helps us keep older appliances alive for longer, but it will also make refurbishing newer appliances more viable. This legislation compels manufacturers to make spare parts, repair instructions, tools and software available to independent repairers. It would help businesses like Appliance Outlet.

Durability labelling

Durability labelling at the point of sale (in-store and online) would mean we could make more informed purchases. A label would also enable brands to compete more directly on durability, creating products that last longer and are easier to repair and refurbish. Similar to the energy rating labels (stars) displayed on large appliances, the durability label would rate products based on their repairability and how long they are expected to last. France already has a repairability index. It assesses if repair instructions and spare parts are available and how easy it is to take a product apart.

How this ends

Manufacturers and retailers have spent decades training us that new is the only worthwhile option. It’s created a world where nearly new appliances – and all the embedded resources contained in them and used to produce them – are thrown straight into a hole in the ground. That should never be acceptable.

The solution isn’t radical:

The used car market is thriving, with many more used cars than new being sold each year. Some people are happy to pay a premium for new, but most will save money and buy older refurbished models. We all accept that, new or older, cars need to be maintained and occasionally repaired. Sometimes a newer model is beyond repair and gets scrapped, but most cars keep going for well over a decade. Manufacturers design them so they can be maintained and repaired through a convenient network of experts. If we fancy a change for something new, or just different, we can sell our current model, or trade it in for something else.

Now change “car” for “appliance” and reread the paragraph above.

There’s a way out of this hole. There’s a way to create a thriving market for durable and refurbished appliances and devices … ending the cut and chuck.

What can we do?

Consumer NZ has introduced ‘lifetime scoring’, using product reliability and owner satisfaction along with our as-new test data to only recommend products that work well for a long time. That’s just the start. We’re also:

Creating second-hand buying guides, using our historical product testing and reliability data to point you to the best used brands and models.

Developing a way to assess appliance repairability – reporting our own ‘durability label’ data to show which appliances are more repairable.

Maintaining pressure on manufacturers by continuing to uncover those who take the easy way out and fail to offer repair or allow resale of used appliances. Watch out for more GPS-tracked appliances!

Supporting the need for a thorough product stewardship scheme for electrical and electronic goods, so manufacturers are responsible for the stuff they make.

Campaigning for legislative change for a Right to Repair and mandatory point-of-sale durability labelling for electrical and electronic goods.

What can you do?

Manufacturers and retailers exist because you buy their products. You have the power to choose what you buy. You can reward those who are working hard to create the future we need and send a message that the cut and chuck is no longer an option. You can:

Shop for refurbished appliances.

Avoid buying the cheapest new appliances. Choose a brand that has refurbished models on sale, lists repair agents, or offers spare parts (all good signs that it supports its products throughout their life).

Avoid manufacturers and retailers who talk about sustainability but fail to walk the talk. Assume it’s greenwash unless you can see real, positive actions being taken.

Support our campaigns for Right to Repair and durability labelling legislation.

The future

Imagine this. In the near future, you’re shopping for a stand mixer. The pricey KitchenAid models appeal, but your budget is more modest. At a local refurbished appliance store (every town has at least one), you see a smart-looking Breville priced at $150. You know the full price of a new one is $450. You also know small appliances are always on ‘sale’, so the new Breville is really worth about $300.

The Warehouse and Kmart sell their own-brand stand mixers for less than $100, but you know neither are a good option. The durability labels that legally need to be displayed next to the price of new appliances tell you those cheap mixers don’t last and aren’t repairable. When they go wrong, they get recycled (thanks to the mandatory product stewardship scheme), but there’s no value in trying to repair one.

The store assistant explains the Breville mixer you have your eye on is only four months old and was a warranty return. She’s proud to be the one to give it a second life. It’s fully tested and, like a new one, it comes in the box with a 12-month warranty. She tells you repairers like this model because it’s easy to fix and spare parts are readily available. You walk out with a bargain.