By Rebecca Styles

Research Lead | Hautū Rangahau

When I spoke to Helen, she was just days away from turning 65, yet didn’t feel like she could call herself a pensioner just yet.

On this page

- How much money will you need to retire comfortably?

- What if you don’t own your own home by retirement?

- What could fix the housing affordability problem?

- Why are women less confident KiwiSaver will be adequate in retirement?

- Recommended changes to the KiwiSaver scheme

- Should there be early eligibility for KiwiSaver?

“I haven’t said I’m retired – I haven’t ticked any box that said retired because in my head, you’re not retired until you’re getting a pension,” said Helen.

She joined KiwiSaver when it was first introduced in 2007. She was working as a teacher aide alongside single parenting.

While she’s saved what she can for her retirement, she worries whether she’ll have enough to pay for day-to-day costs in a cost-of-living crisis.

“When I think of the cost of living in retirement and how, from year to year, the cost of living goes up, will I have enough?”

While NZ Super is a fixed amount, she plans to reinvest her KiwiSaver balance. Any income she earns from that will be variable.

How much money will you need to retire comfortably?

It’s no wonder such questions are playing on Helen’s mind because it’s unlikely NZ Super will cover all her expenses in retirement.

If you live alone, there’s a $193.17 shortfall between NZ Super and the estimated weekly spend in a region. If you want a few luxuries, you’ll need to find another $766.98 a week.

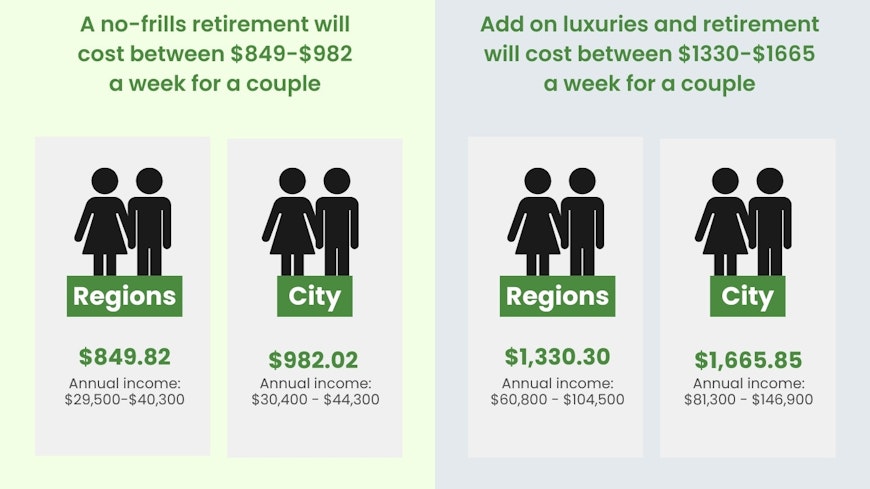

The figures are calculated annually by the NZ Fin-Ed Centre based at Massey University and use the 2023 NZ Super rates. In its 2023 update, a retired couple on a no-frills budget would need $849.82 a week if they’re living in the regions on an annual income of between $29,500-$40,300. For those in the city, it’s $982.02 ($30,400 - $44,300 pa).

If you want to have a few luxuries, the weekly allowance for a couple is $1,665.85 if you live in the city ($81,300 - $146,900 pa), and $1,330.30 if you live in a smaller centre ($60,800 - $104,500 pa).

But those guidelines allocate just over 19-30% for housing costs for a couple in the city (after tax), which includes maintenance, rates and power. If you’re renting in retirement, the percentage of your weekly budget dedicated to housing will likely be considerably higher.

What if you don’t own your own home by retirement?

Bronwyn (52), a Wellingtonian, recently got an update on her KiwiSaver balance, prompting her to work out how much money she’d need by 65.

“If I was solely relying on my KiwiSaver, I’d be toast. If I was relying on my KiwiSaver and superannuation, I’d be toast with jam,” she said.

What’s causing more concern is that she rents and won’t own her own home by retirement. While she’s paying below market rent now, that’s likely to change.

“I do have a marquee,” she joked. While she is trying to keep positive and see the funny side, she finds the prospect of financial vulnerability in retirement a bit “stark and overwhelming”.

The assumption has been that most people will own their own homes by retirement, but with decreasing levels of home ownership, this is unlikely to be the case in the near future.

Retirement Commissioner Jane Wrightston said late last year that based on current trends, 100% more people – 600,000 older people in total – are expected to be paying rent in retirement in 2048 than in 2020.

She also noted that one in five people are now paying a mortgage after the age of 65.

Of those still paying mortgages in retirement, 80% are spending more than 40% of their NZ Super on housing costs. More than half are spending 80%, according to the Retirement Commission’s Review of Retirement Income Policies 2022.

For those renting, two-thirds spent 40% of NZ Super on housing, while for some, it was as high as 80%.

For retirees who owned their own home, over half spent less than 20% of their NZ Super on housing.

If people are spending so much on housing from their NZ Super, they’ll need to rely on their KiwiSaver, or other savings, to ensure they have a good quality of life.

Yet, the Retirement Commission’s analysis has shown the KiwiSaver balances for a fifth of 51-65-year-olds are less than $10,000.

It also noted that KiwiSaver has only been around for 15 years. It won’t be until 2054 that the first person who has contributed to KiwiSaver for their entire working life turns 65.

What could fix the housing affordability problem?

Housing costs aren’t going down anytime soon – so what can be done to help people pay for housing?

While some people will have access to investments other than KiwiSaver, for those who don’t, the Retirement Commission has suggested changes to the Accommodation Supplement (AS).

Currently, the AS is means tested, and the limit of cash assets – such as savings, shares or stocks – is $8,100. This means when you’re 65 and your KiwiSaver becomes available, it’s counted as a cash asset.

The maximum cash asset limit hasn’t changed since 1993 and isn’t adjusted for inflation.

The Retirement Commission recommends increasing the cash asset limit to at least $42,700 per person. It would also like the government to consider making annual inflation adjustments to the limit.

These adjustments, along with ensuring an adequate supply of affordable housing, will go some way to help those who are struggling to cover their costs in retirement.

Why are women less confident KiwiSaver will be adequate in retirement?

Our recent KiwiSaver survey found just 8% of respondents aged 60-69 years were confident their KiwiSaver balance would be enough to retire on.

Across all age groups, women are less confident than men. The gap in confidence levels between the genders has grown over the past five years.

The lack of confidence could be related to the job market and parenting. Time away from paid work means some women don’t have the same number of years in the workforce to contribute to their KiwiSaver balance.

Kay Saville-Smith is the research director at the Centre for Research, Evaluation and Social Assessment (CRESA).

“I think what happens for women is that they already have a disadvantage in the labour market – the pay rates are less, so therefore their rates of saving are likely to be less,” she said.

She sees this as a disadvantage in the labour market, rather than with KiwiSaver itself.

Pay equity in what are traditionally seen as feminised roles, like childcare and health, will help address some of those issues, she said.

Associate Professor Claire Matthews is the Director of Academic Quality at the Massey University Business School. She agreed the KiwiSaver scheme has some unintended inequities rather than being inequitable.

“The reality is that yes, people who aren’t working full-time don’t necessarily get the same benefits. And if you have to take time out either for children or to look after your parents … you’re going to be disadvantaged. KiwiSaver doesn’t make any assumptions around that – whether it should, is the question.”

Recommended changes to the KiwiSaver scheme

The Retirement Commission proposes a few changes for employers, government and financial services to make KiwiSaver fairer for women.

It would like more independent financial advice available to women.

It also recommends that employers could:

address gender and ethnic pay gaps in their businesses

pay the employer contribution when an employee is on parental leave (currently there is no obligation for employers to do so)

help staff, when it’s financially possible, make voluntary contributions to ensure they get the government contribution.

The Retirement Commission also recommends that the government could remove the minimum payment for those on paid parental leave to ensure they get the government contribution of $521.43 each year. At the moment, you need to have paid $1,042.86 a year to get the government contribution.

If you don’t meet the minimum payment, the government will contribute 50c for every dollar you save.

In one change to the scheme, the government announced in this year’s budget it will pay the KiwiSaver employer contribution for people on parental leave who continue to contribute to the scheme.

We think another aspect of KiwiSaver contributions could be reviewed. Currently, employers aren’t required to contribute to your KiwiSaver if you keep working at 65 or over. In most cases, the government’s contributions stop, too.

Yet, if people are staying in work longer because of rising costs, we think this could be revisited.

Should there be early eligibility for KiwiSaver?

Associate Professor Matthews also pointed out other potential inequities around the age of eligibility for KiwiSaver (65 years).

“The fact is that for some people, the type of work they do or their health situation means that their chances of getting to age 65 are reduced … or, if they get to 65, they’re not actually going to have as long a retirement as other people.”

This eligibility age particularly affects Māori and Pacific people whose life expectancy is less than Pakeha.

While there could be an opportunity to look at the ability for some people to access their KiwiSaver balance earlier, it would be difficult to decide on the criteria to do so, Associate Professor Matthews said.

While this isn’t one of the Retirement Commission’s recommendations, it does think more research should be done to consider retirement income policy changes for Māori.

It’s also recommending several initiatives to support Māori and Pacific people in retirement:

Ensuring affordable housing which enables multigenerational living is available.

Investigating how financial services could better support collective ownership of homes.

Developing more programmes to help people plan for retirement.

What the Retirement Commission, Associate Professor Matthews and Dr Saville-Smith all agree on is that NZ Super needs to be maintained at current levels for everyone.

Which bank is best?

We asked consumers to rate satisfaction with their bank. How did yours do?